The answer is: 300,000 km² of land. We need a total of 300,000 km² (approximately 550 km x 550 km) of land to power the entire planet with solar panels.

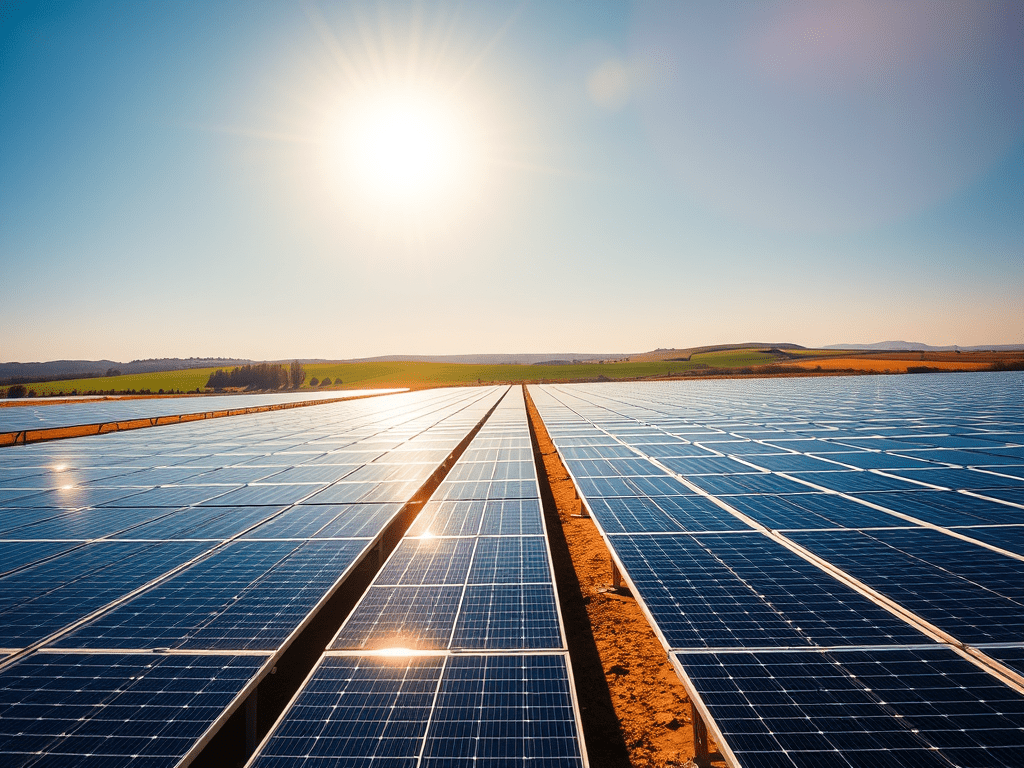

Currently, solar farms require 2 hectares (5 acres) of land per 1 MW solar farm. Newer solar panels have reduced this requirement to 1.3 hectares (3.2 acres) per 1 MW solar farm. For a 10 MW solar farm with a 100% capacity factor, 10 km² (10,000 hectares) of land would be necessary. The calculations for this area are shown below.

In a region with an average hourly output of 100 W/m² (e.g., Melbourne, Australia), 1 km² of land covered with solar panels can generate 100 MW of power. Considering the annual average of 6 hours of sunshine (e.g., Melbourne, Australia), an additional 6 km² of solar panels are required to produce electrolytic hydrogen during these six hours. This hydrogen is used to generate fuel cell-based power for the remaining 18 hours with a round-trip efficiency of 50%. Another 3 km² of land is reserved for the balance of plant and inter-panel spacing, bringing the total land area requirement to 10 km² and solar panels to 700 MW nameplate capacity for 100 MW of baseload power. A land area of 10 km² for 100 MW is similar to the requirement of a concentrated solar thermal power station with 18 hours of storage. Therefore, just 1,000 km² of land can generate 10 GW of baseload power. This land area is comparable to the footprint of hydroelectric power stations. For instance, the Three Gorges Dam has a surface area of 1,084 km² and a nameplate capacity of 22.5 GW with a 45% capacity factor.

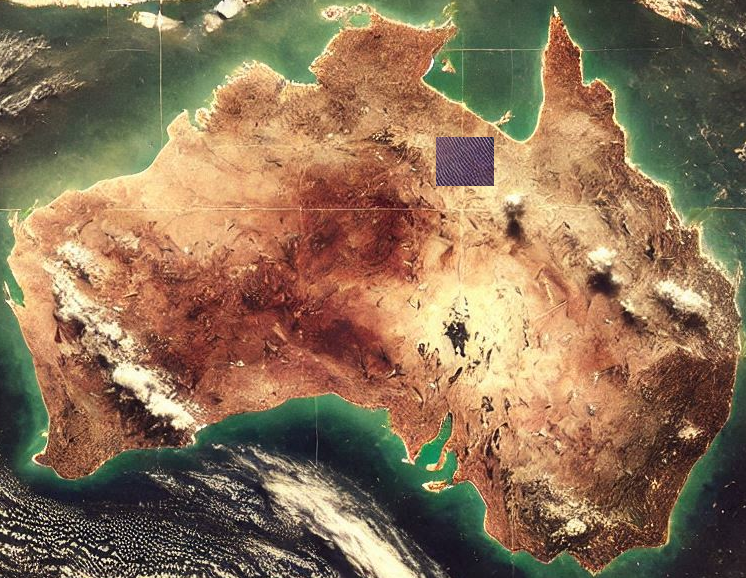

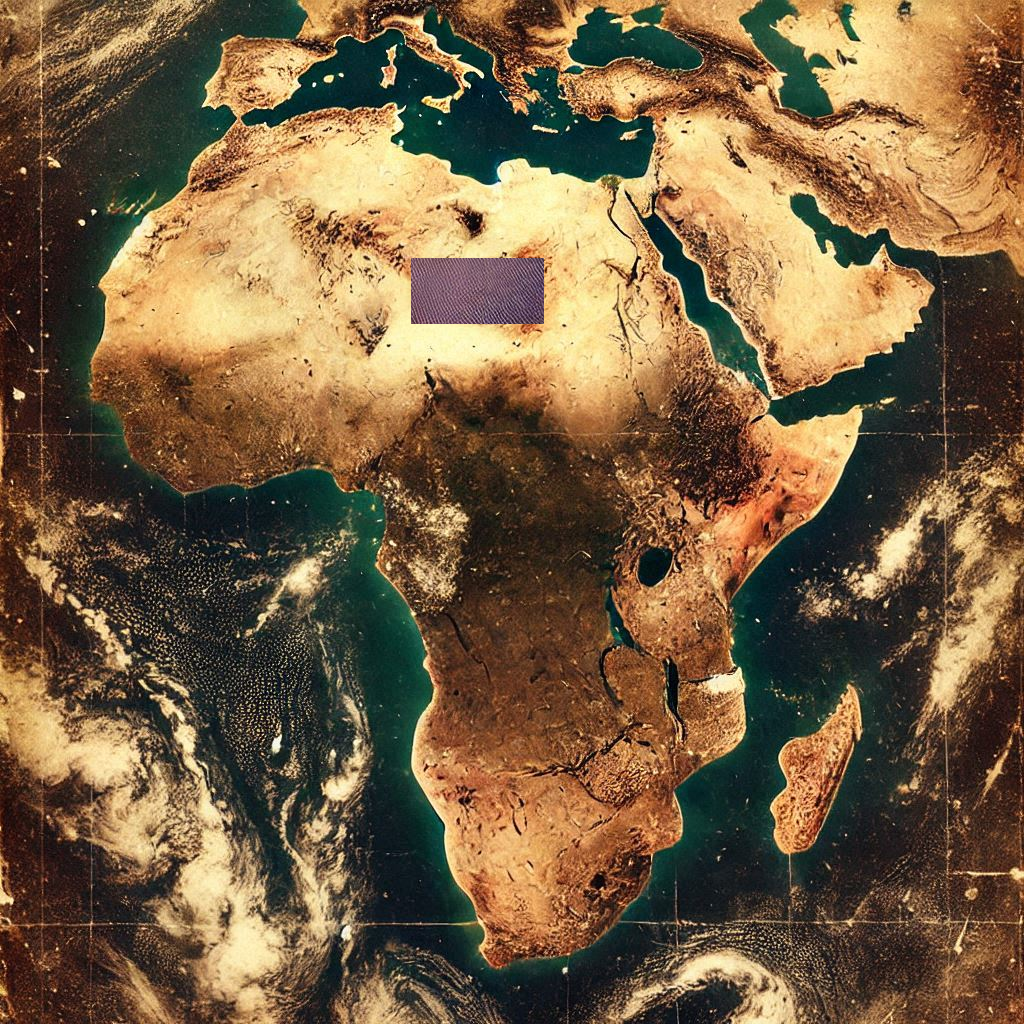

Theoretically, 300,000 km² (approximately 550 km x 550 km) of land could meet the entire world’s baseload power demand of 3 TW (excluding transport). This area is equivalent to the size of Norway, Poland, Oman, or roughly the size of New Mexico or Arizona in the United States. It corresponds to 3% of the Sahara or 4% of Australia’s surface. Power output would be higher if energy storage in the form of hydrogen is not considered, due to a 50% loss in round-trip efficiency. Additionally, regions like the Sahara, with higher solar irradiance, would yield even greater power output. Increases in PCE would further increase the output. While it is impractical to produce the entire planet’s power in one location, this provides a bird’s eye view of the minimal footprint required to convert the global economy to renewable power.

Wind energy hasn’t yet matched the footprint efficiency of other sources. However, larger and more efficient turbines are key to providing baseload capacity. The SUMR-50, a 50 MW turbine, captures more energy with its larger rotor and advanced materials, reducing the number of turbines needed. Similarly, the anticipated 100 MW turbines promise even greater efficiency and power output, matching the footprints of hydro and solar power.

Reference

To Cite: Adeerus Ghayan. “Orycycle.” Islamabad: Subagh (2018).

The entire article is taken from Adeerus Ghayan’s book Orycycle.

Amazon Link: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07MDS544V

Also See

Ghayur, A. (2023,). Biosynthetic organic solar cell biorefinery to fulfil Australian baseload power demands. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Energy Technologies for Future Grids. Australia

Can Solar Panels Power Every Home on Earth—Day and Night, Affordably?