I’m completely at ease crafting one-dimensional Mary Sues and Gary Stus, simply because they’re the easiest characters to write. But that ease comes with a hidden cost. It doesn’t reduce the overall workload—it just shifts it. Because when your characters lack depth, the plot has to carry everything. Every scene, every page needs to be packed with momentum, tension, surprise or humour. There’s no room for filler. The story has to be so engaging that readers don’t stop to question the character’s lack of vulnerability or complexity.

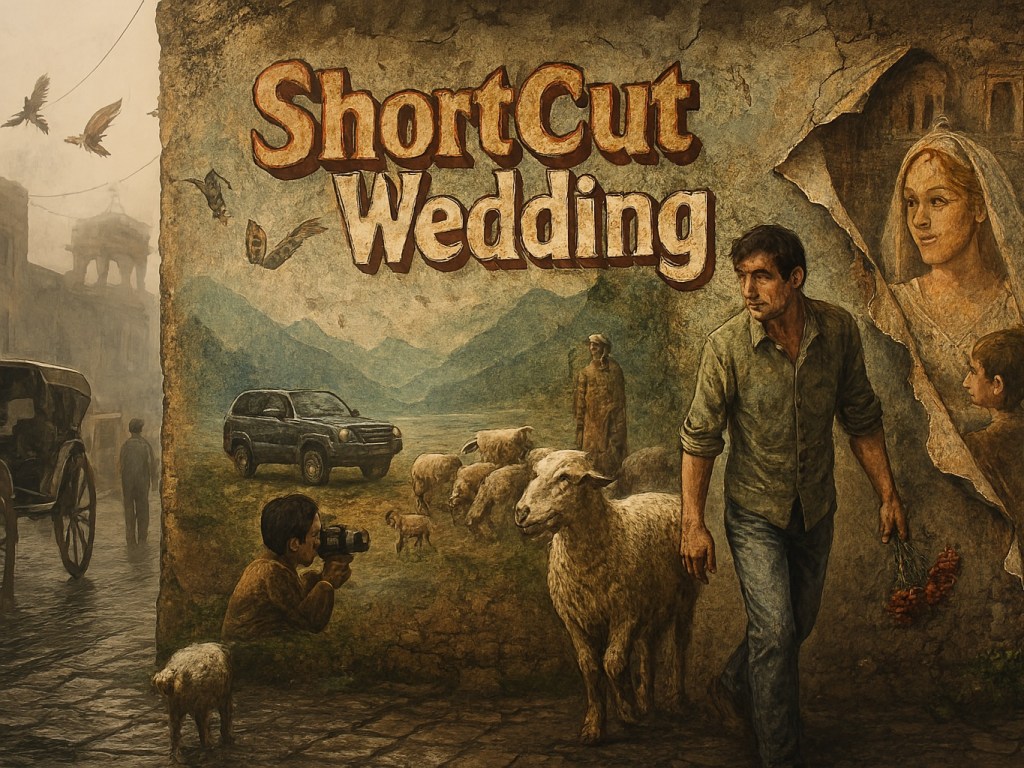

And that’s the paradox: the more invincible and perfect the character, the more strain the plot must bear to keep the story compelling. You lose the fear of death, failure, or moral compromise—but you gain the challenge of crafting a world where their success still feels earned. That means every twist, every escape, every resolution has to be logically coherent and emotionally satisfying. If it breaks the rules of the fictional world, the illusion collapses. But if it holds together, it becomes entertaining in a very specific way. That’s exactly what I set out to do in Shortcut Wedding—a romantic comedy set in the misty mountains of northern Pakistan in the mid-1990s. The story’s momentum, tension, humour and coherence had to compensate entirely for the fact that it rests on the shoulders of a single Gary Stu. And paradoxically, that constraint is what makes it so entertaining.

There’s another reason I enjoy writing one-dimensional characters: they don’t need an arc. They’re fixed, unchanging, and that fits my creative style. I’m not interested in forced growth or redemption arcs. I’m interested in structure, pacing, and integrity of the fictional world. And despite how effortless a one-dimensional character might seem, building an entire story around one and keeping it entertaining is a serious challenge. In Shortcut Wedding, I deliberately kept the hero as flat as possible, just to test the limits of what plot and structure alone could achieve. And I’m happy to say, it turned out exactly as I’d hoped. Believe it or not, I wrote it thirty years ago, and even now, when I revisit it, I still enjoy it. For me, that’s the core metric of a good novel: if it still holds your attention decades later, it’s done something right.

And that’s the core of it: enjoyment and sustained attention. I’ve written many other books—some decades ago—that remain unpublished. Why? Because every time I revisit them after a year or ten, I find myself wanting to overhaul major sections. They lose me somewhere along the way. And if they can’t hold my own interest, I won’t ask others to read them. So, who knows when—or if—they’ll ever come out.

But enough of that tangent. Let’s get back to Shortcut Wedding—and why it works. If you’re familiar with my writing, you’ll notice a pattern: I love opening with a strong hook. It’s instinctive. I want readers to feel pulled in from the very first line. Shortcut Wedding is no exception.

The second challenge was structural. When a Mary Sue or Gary Stu dominates every scene, no matter how entertaining they are, it quickly becomes too much. Readers need contrast, rhythm, and space to breathe. So even though the story rests entirely on one character’s shoulders, I kept shifting the point of view to other characters. These scenes weren’t about the hero directly, but they were shaped by his influence—his actions, his reputation, his ripple effect off-screen. That way, he stayed present without becoming overwhelming.

Third, I leaned into his invincibility and perfection—but only in ways that amplified the entertainment without breaking the logic of the world. That balance was crucial. Because once the fictional framework collapses, once the internal rules stop making sense, that’s when Mary Sues and Gary Stus lose their grip on the audience.

Fourth, I brought in something personal—my own lived experience. The time I spent in Northern Pakistan, journeying through remote valleys, witnessing local traditions, and absorbing the quiet dignity of rural life, left an imprint that shaped the soul of the story. That texture—that lived-in authenticity—infused every scene with emotional weight and cultural depth. It transformed Shortcut Wedding from a simple romantic comedy into something more layered: a cultural snapshot, a tribute to a region often overlooked, and a love letter to a place and time that still lingers in memory.

Together, these four elements turned a one-dimensional Gary Stu into something memorable and enjoyable. And to date, I haven’t met a single reader who didn’t finish the story. For me, that’s a strength. But if you’re one of the few who couldn’t get through it, I genuinely want to hear why. I welcome critique. I want to understand what didn’t work for you—because that’s how I grow as a writer.

Before I wrap up, there’s one more thing worth mentioning. Shortcut Wedding was written long before the cultural debates around wokeness, diversity, cancel culture, and progressive agendas became central to storytelling discourse. It predates the binary framing of being “for” or “against” these themes. That makes it an interesting artifact—a window into how a writer approached narrative thirty years ago, without the weight of today’s ideological battlegrounds.

It also offers a contrast to my more recent work, like Nureeva and Tangora, and my video “Why Nureeva and Tangora Isn’t Harry Potter—and Why Everyone Enjoys It.”

Also See

Flawless to Flawed Spectrum of Fictional World Building in Novels and Media

Best Opening or First Lines of My Novels

Shortcut Wedding Shows Even One-Dimensional Mary Sues and Gary Stus Can Entertain